How the Arbatel Spirits Got Their Names

The Arbatel is one of the most influential books on ritual magic ever written. But where does it get its strange spirit names—Bethor, Phul, Haggith, and the rest? Two words: tabula recta.

Buckle up, bastards. It’s about to get heavy.

The Arbatel, first published in 1575, may be the most influential book on ritual magic ever written. Its straightforwardness has made it popular since its first appearance and it is a common choice as first grimoire for budding occultists.

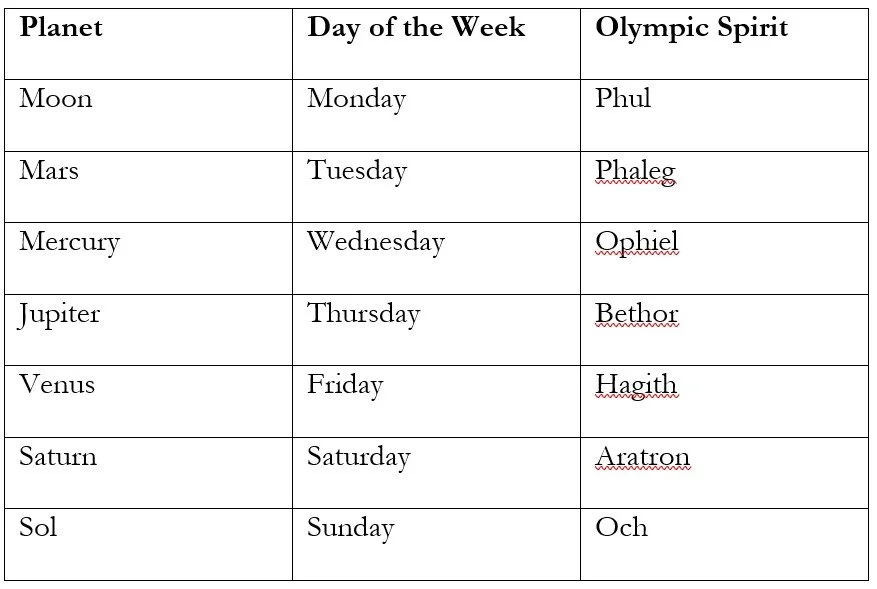

The Arbatel presents (among other things) the “Olympic spirits,” seven powerful beings “by whom God hath appointed the whole frame and universe of this world to be governed” (Turner’s 1655 translation). There is one spirit for each of the Ptolemaic “planets”—the sun, the moon, and the five planets of the solar system known at that time.

Now, we know of no grimoire before the Arbatel that uses these spirit names. Nor do these spirit names come from any known mythological system. Nor do they all come from the same language. Hagith might be Hebrew—it is, in fact, the name of a minor character in the Hebrew Bible—and Bethor might plausibly be derived from the Hebrew, as well. But Ophiel and Aratron both seem Greek, and the possible linguistic derivation of Phul is anyone’s guess.

The names seem varied, weird, and arbitrary. So where did the author of the Arbatel get them? Revelation? The random scattering of letters? Speaking in tongues? The mouths of the spirits themselves? Where did these weird names come from?

The answer to this question is easy once we remember one important fact: the history of the occult is tightly interwoven with the history of cryptography. Where we find codes and ciphers written about in the early modern period, we will frequently find the occult written about, too.

Consider Johannes Trithemius (1462-1516). He is sometimes called the father of modern cryptography, in part because he published the first printed work on the subject; he also numbered among his students the occultists Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and Paracelsus. There have been lengthy scholarly arguments about whether his most famous work, the Steganographia, is about magical spirits or about codes and ciphers.

For our purposes, Trithemius’s most important contribution is the cipher that bears his name. If you fiddled around with codes and ciphers as a kid like I did, you probably worked with simple substitution ciphers: A=1, B=2, and so on. You encode your message into numbers, and your recipient uses the cipher to get the message back. Or you may have seen the so-called Caesar cipher, in which each letter of a message is shifted down a certain amount—say, five letters. Thus, an A in the message would be replaced by an F, a B would be replaced by a G, and so on.

Such simple ciphers are easily broken because some letters are more common in English than others. If you see a particular character showing up a lot, it is probably a common letter like E, A, T, or S, for example. Trithemius had a bright idea for complicating things. What if instead of just a single cipher, the person writing the message used several? And this is where the tabula recta comes in. This is a table with 26 alphabets written on it in rows, with each alphabet shifted over one space relative to the one above it.

You could start at, say, the sixth row. You encode the first word of your message using this row of the tabula recta. But instead of encoding the whole message this way, you can shift down—say, four rows, ending up at row 10—to encode the second word of the message. Go down four more rows, to row 14, in order to encode the third word, and so on. Basically, instead of being a simple substitution cipher, the Trithemius is a polyalphabetic substitution cipher, making it very much harder to break.

And here is the point: whoever wrote the Arbatel used a tabula recta—a Trithemius cipher—to get the names of the spirits.

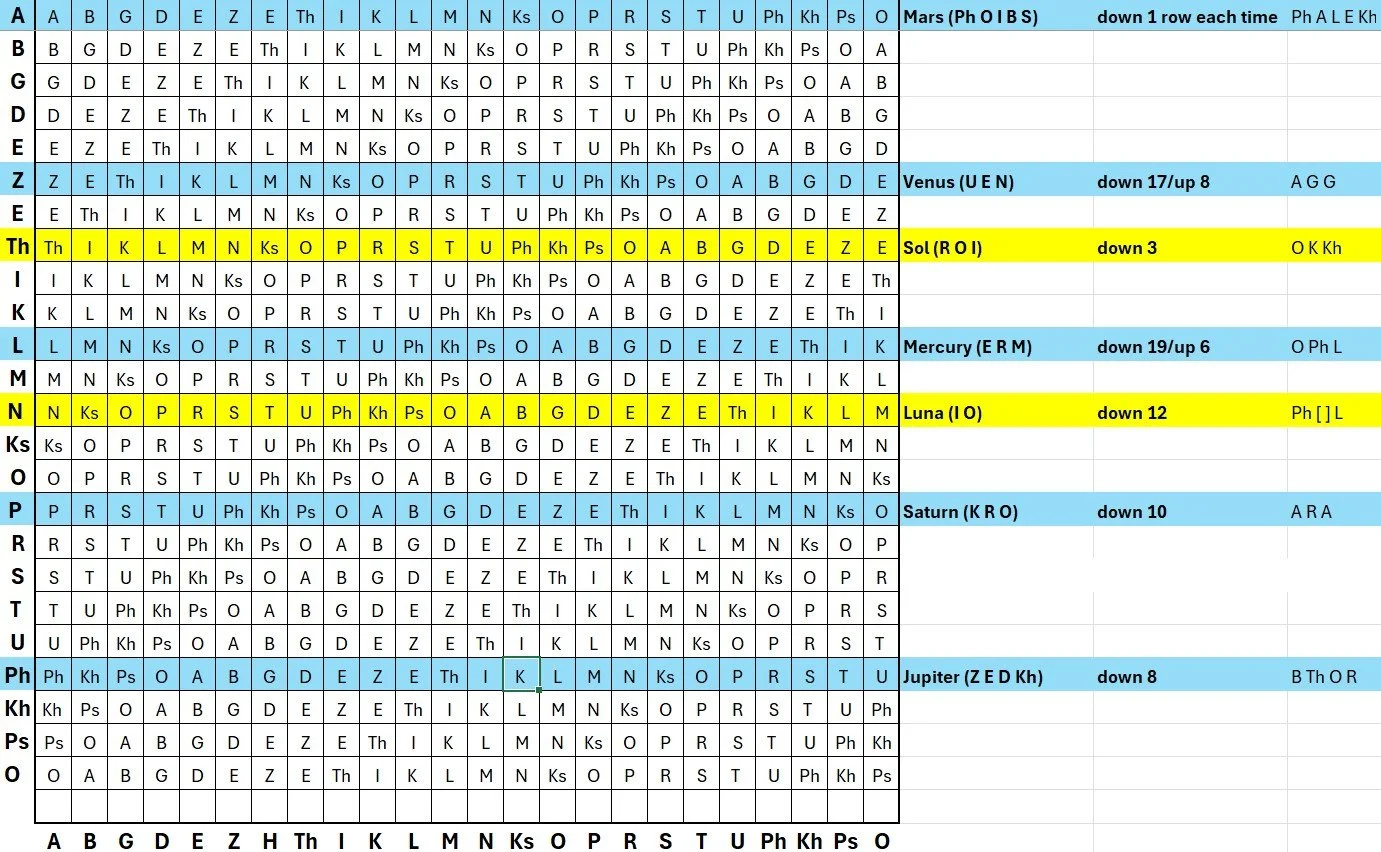

Now these are “Olympic spirits,” “spirits of Olympus,” spirits whose names come from “the Olympic speech.” Greek, right? Our tabula recta will use the Greek alphabet of 24 letters, and not our Roman alphabet of 26. Here it the tabular recta used by the author of the Arbatel, whom we will call François since scholars believe that he was a French Paracelsan.

(Since many people lack intimacy with the Greek alphabet, I have transliterated the letters into rough phonetic equivalents: alpha is A, beta is B, epsilon and eta are both E, omicron and omega are both O, and so on. The only peculiarity is that a blank line is added, so that the tabula has 25 rows instead of the 24 you’d expect from its use of the Greek alphabet.)

Tuesday, named after the Norse war-god Tyr, is associated with Mars (in Latin, Dies Martis). For whatever reason—there may be a clear justification or it may be arbitrary, I’m still investigating—François started with the first row, where alpha = alpha, beta = beta, and so on. François then went down by one alphabet for each letter. And what did François encode in order to get the spirit-name Phaleg? Sensible choices like Ares, Mars, and Tyr appear not to have worked, so he (he?) cheated a bit and used Ph O I B S—perhaps because of the common confusion of Apollo’s epithet Phoebus and the name of Ares’s son, the fear-god Phobos. Starting at row 1 and going down one row for each letter, the result is Ph A L E Kh (phi alpha lambda epsilon chi).

Wednesday is associated with Mercury (Dies Mercurii). The writer started at row 11 and went down 19 rows (or up 6 rows, same difference) for each letter. The text being encoded was E R M, the first three letters of Hermes’s Greek name (the H sound was done with a diacritical mark). The output? O Ph L.

Thursday, Jupiter, starts at row 21 and goes down 8 rows for each letter. Here the author cheats a bit by using (roughly) the Hebrew word for the planet Jupiter, Tzedek (Z E D Kh). The output is B Th O R.

Friday, Venus, really should start at row 31 to keep the pattern going. Unfortunately, there are only 25 rows in our tabula recta. So we wrap around, and Venus starts at row 6, and it goes down 17 rows (up 8 rows) for each letter. The input is Venus, or at least the first three letters of that name: U E N (upsilon is the most sensible choice for the V that the Greek alphabet lacks). The output is A G G.

Saturday, Saturn, begins, as we might expect, on row 16. It goes down 10 rows for each letter. The input is the first three letters of Kronos’s name, K R O, and the output is A R A.

Some things to notice: first, going in order of the Latin days of the week, the starting row is 10 down each time: Tuesday’s spirit starts at 1, Wednesday’s starts at 11, Thursday’s at 21, and so on, as we have already seen.

Second, François sometimes struggles to find a good spirit name. We see him using both Hebrew and Greek, and even stretching things a bit (Ph O I B S for Ares). It is as though François has stuck himself with a system for what row to start on and how far down to go for each letter, and this rigor makes good spirit names harder to derive from the tabula recta. (Again, I have not yet been able to figure out what decides how many rows the writer moves down with each new letter.)

Third, François frequently just uses the first three letters of plaintext to produce the start of a spirit name, then slaps on a suffix. Thus the tabula recta gives him A G G for the Venusian spirit, and he slaps on the Hebrew suffix -ith. A R A gives the Saturnian spirit, and he slaps on the Greek suffix -tron. He seems to feel that getting a workable trio of letters is close enough for government work.

But this just gives us the five planets. What about our solar system’s two luminaries, the sun and the moon, Sunday and Monday? Here, I confess that I am puzzled. It is clear to me how the names were derived, but not why.

Thus, our writer uses the French word for king (transliterated into Greek) to get the name of his solar spirit—R O I yields O K Kh—which suggests a lot of difficulty getting his cipher to give him a workable output. Why not use an input like Apollo, Helios, or Sol? Similarly, the writer uses Io’s name to get Ph [ ] L, where the middle letter falls on the blank row. Why not instead use Selene, Luna, or Levanah? François seems to be stuck starting from a particular alphabet and going down a particular number of rows each time, so that he has a hard time getting a spirit name that works.

But why should the name of the solar spirit start at row 8 and go down 3 each time? Why should the lunar spirit start at row 13 and go down 12 each time?

I have absolutely no idea.

But be that as it may, this is how the writer of the Arbatel derived the names of his spirits. A Trithemius cipher, a tabula recta, using the Greek alphabet.

Yeah, I did this in Microsoft Excel. You want to make something of it?

This answer opens up all kinds of new questions, however. What determines how many rows to go down each time? Why doesn’t anything seem to start on rows 3, 18 or 23? Might the author’s own name be encoded in this tabula recta? And might the title of the Arbatel be itself derived from this table, as well?

And then there is the question of how generalizable my finding is. Might the names of at least some spirits in other grimoires be similarly derived? When we see Goetic demons with names like Gaap, Aym, Ipos, and Bune, are we in fact seeing the outputs of another tabula recta? Or perhaps something fancier, like a Vigenère cipher?

I will be interested to see where further research in this area takes us. I would also be interested to see if anyone else has independently figured out the derivation of these spirit names—in retrospect, the answer seems so obvious.

And if you develop new insights about how the Arbatel author used this tabula recta, do let us all know!

Adverbs Are Not Your Real Enemy

Every good writer says the same thing: adverbs are the enemy of good writing.

But though they are treacherous, adverbs are not the real enemy of effective prose.

Here’s what is.

The Geiser Adverb Thresher (Wikimedia Commons)

Any successful writer will tell you the same thing: adverbs are the enemy of good writing.

Stephen King tells us that the road to hell is paved with adverbs. Elmore Leonard calls their use “a mortal sin.” And though no one seems to agree on which famous writer said it, some famous writer or other said that “If you are using an adverb, you have got the verb wrong.”

But what is an adverb, exactly? You need to know what they are to avoid them, after all.

Well, to review what you probably learned in childhood, an adverb is simply a word (usually ending in -ly) that modifies a verb: happily, groggily, slowly, vigorously, and so on.

· Except for the words ending in -ly that are adjectives, not adverbs (cowardly, earthly, manly, yearly);

· And the adverbs that don’t end in -ly (seldom, somewhat, today, upstairs);

· And the adverbs that never modify verbs (hardly, rather, vastly, very);

In short, if you put together a list of common adverbs in English—also, quickly, tomorrow, well, finally, etc.—you would only find one single quality shared by all of them: each one modifies something or other that is not a noun. That’s it. They share nothing else in common—neither their form nor their function nor where they can appear in a sentence. Adverb is a grammatical blob. It is not a part of speech at all.

And what’s so bad about using adverbs anyway, even if we assume that the category is not an overfilled garbage can (which it is)? Every page of English prose by every author in existence has at least one or two, so why should budding writers try to avoid them?

As Obama says, Let Me Be Clear: Stephen King and Elmore Leonard are actually kind of right about adverbs.

The overuse of adverbs slows down your writing (adjectives, too). It also indicates a lack of care and revision, since a modifier and the word it is modifying can frequently be revised into a single word: shouted instead of said loudly, immense for very large, etc. Adverbs really are treacherous. They make your prose tedious. You should write with verbs and nouns instead.

But though adjectives and adverbs gum up your sentences and make your prose turgid, they are not the real enemy. Not really.

The real enemy is modifiers that modify other modifiers.

Consider the phrase very few applicants. The main word here is the noun applicants. Without getting into arguments about what part of speech few is here, we can say at least that it modifies applicants. And very, of course, modifies few. And if modifiers slow down your prose (which they do), modifiers that modify other modifiers slow it down even more. Before we get to that main noun applicants, we first have to get through the modifier few; but before we can even get to that modifier, we have to get through its modifier, very. It’s as though the main noun has a doorman, and you don’t even get to see the noun’s doorman until you’ve gotten through the noun’s doorman’s doorman.

So here’s what I suggest. Linguists, grammarians, y’all can do your own thing, it’s none of my business. Been nice having you, drive home safely. Bye now.

But writers, perhaps you ought to think about modifiers in this way:

· A modifier that modifies a noun is, by definition, an adjective (red, octagonal, horse-like, furtive);

· A modifier that modifies a verb is, by definition, an adverb (seldom, upstairs, groggily, playfully);

· A modifier that modifies something other than a noun or a verb IS NOT AN ADVERB, DAMMIT! You don’t get to just throw all the leftover words into a category like a meth-head on garage sale day!

· A modifier that modifies other modifiers—very, rather, somewhat, hardly—is, let’s say, a modulator. (I’d call them intensifiers, except that some are important in hedging. Note that traditional grammars usually call these words adverbs of degree, which makes me angry but I’m letting it go. I’m letting it go.).

· Finally, just to be complete, a modifier that modifies an entire clause (hopefully, unfortunately, luckily) we can call a sentential (terrible name, feel free to suggest alternatives).

The short version: adjectives and adverbs are essential, but must be used sparingly. If your prose is boring, find adjectives and adverbs to cut and your nouns and verbs will be able to move the reader along your sentences more smoothly and enjoyably..

Modulators, on the other hand, should be slaughtered like crab lice: mercilessly, thoroughly, and with absolute faith in the moral rightness of your actions. If one of these vile words begs for its life and provides compelling reasons to spare it, murder it anyway. If its supplication and reasoning give you pause, allow yourself the luxury of murdering it during the next round of revision instead—but leave yourself a note so you don’t forget.

As Mark Twain famously says, anytime you feel tempted to write the word very, replace it with the word fucking. Your editor will cross the word out and your prose will thereby be improved.

(I may be paraphrasing slightly.)